How to achieve attuned, age-appropriate parenting?

By Sapna Matthews, Assistant Senior Counsellor

Most moms and Dads describe the moment they saw their child’s face after delivery as a moment of deep emotions. As they hold their fragile, tiny newborn, I strongly believe that the parent genuinely hopes to be the best parent they could be. Of course, as the years tick by, there can be fluctuations in the parenting journey. The downs in the parenting could perhaps be the parent’s experience of stressors, their inadequate understanding of their

parental role, and perhaps their own adverse childhood experiences. Even though there is no perfect parent, I do want to believe that every parent has the potential to be the best parent for their child. So, how can we work towards becoming that?

Adverse Childhood Experiences correlated with higher health risk

Before I share my own parenting journey, I would like you to stay with me while I bring out some pieces of research and findings. Let me begin by stating the big “Red Flags” that can affect the child’s mental and physical health in the present and in the years to come. They are called the “Adverse Childhood Experiences”, or ACEs. An ACE describes a traumatic experience in a person’s life occurring before the age of 18. These include physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, mental illness of a household member, problematic drinking or alcoholism of a household member, illegal prescription drugs use by a household member, divorce or separation of parents, domestic violence between adults in the household, incarceration of a household member. Exposure to any one of the above ACE is counted as one point. Research has shown that, as the number of ACE increases, the risk of health problems increases. Anxiety, depression, obesity, diabetes, smoking, heart disease, and chronic drinking all seemed to have a correlation with a higher ACE score.

You may wonder what the reason for this correlation could be. It is the way the brain is structured to respond to its environment and the people in it. As a child, how the brain responses to stress is still under development. Typically, in the face of stressors caused by ACEs, say a parent who is physically abusive, the child’s body feels he is not safe, and will respond by producing stress hormones such as cortisol. Prolonged and persistent elevated cortisol levels are linked to lower cognitive performance in young children along with lower immune and metabolic functioning. Cortisol elevation causes damage to the hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for learning, memory, and emotional regulation.

Subtle signs of parents’ emotional abuse and neglect

Ok, so now we know that ACEs has long term consequences for the brain and body. As a parent, we might think that we’re doing good: we don’t use drugs, have never been incarcerated, and consciously stay away from physical abuse.

However, there are two ACEs that are more sinister because of their subtlety. Emotional abuse and emotional neglect. I tend to resonate with these two, as these are the easiest to miss as a parent. In the ACEs questionnaires these two would get highlighted if a child answered accordingly (Yes/No) for these questions:

- People in your family called you things like “lazy” or “ugly (Yes)

- You felt that someone in your family hated you or threatened to harm you in some way (Yes)

- People in your family said hurtful or insulting things to you, swear at you, insult you, or put you down (Yes)

- You didn’t have someone in your family who helped you feel important or special (Yes)

- You knew there was someone to take care of you and protect you (No)

So, what exactly is emotional neglect? It’s the ongoing pattern of failing to provide connection, support, and adequate responses to distressed behaviours of the child. For example, demeaning a child for their emotions, (e.g., calling them a “cry-baby”) makes them feel that their emotions are wrong or unimportant. Another example could be, when your child comes to you to share something important about how their feeling or about their day, you stay glued to your phone or laptop. This could be particularly hard because many of us carry work home with us. However, the subtle message the child receives is that what they have to say is not important or that their emotions should not be shown.

For children, research has shown that affectional neglect can cause failure to thrive, developmental delays, hyperactivity, aggression, depression, low self-esteem and other emotional disorders. Signs of emotional neglect could be low self-esteem, difficulty regulating emotions, heightened sensitivity to rejection, negativity towards parents, social withdrawal, frequent tantrums, aversion to affection etc. Consistent emotional neglect can wear down the stress response systems and bring down cortisol levels, leading to depressive symptoms, anxiety, and in extreme cases, Addison’s disease. All of us need right amounts of cortisol to perform. However consistent elevated levels or low levels could cause psychological problems.

In Singapore society where life is hectic and time is a precious commodity, there is a tendency to feel that by providing for the child’s physical needs, paying and taking them for enrichment classes, and making sure that they behave well enough in the classroom is sufficient.

Little things you can do to be emotionally present for your child

It’s true that those are important. But sometimes it’s the little things that can make all the difference to the child. For instance, putting down the phone and giving your child your attuned attention when they have something important to say about their day. I have found in my own parenting journey, that putting away my phone or any digital device for the first 1-2 hours after returning home from work, could make a world of difference to my children. Another way could be by sharing your life stories, not just the “hero” stories, but also the times when you messed up, big time. These stories help your child build empathy and understand the importance of choices and consequences.

When you have to discipline them, make sure you are regulated and calm first. Your tone should be firm, but not angry. The moment a child hears anger in a parent’s voice, his fear response goes up, shutting off his prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that’s needed to analyse his actions or behaviours. That angry tone could make it impossible for your child to learn the lesson you are trying to teach. I have also seen parents expecting behaviours that are more likely to be found in a much older child for a 3-year-old. For example, wanting a child to sit still for period of time is unreasonable for a very young child.

As a parent, the hardest years were when my children hit their teenage years. Compared to the teens, the terrible twos and troublesome threes seemed like a piece of cake. It didn’t help that each child had a different temperament and personality. I must confess I have felt like a failure many times during this period.

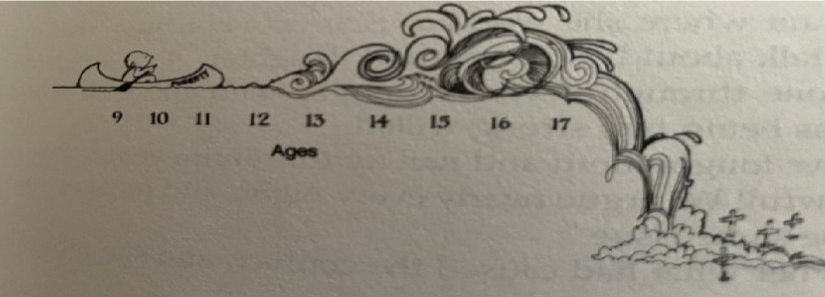

Let me share a piece of knowledge I gleaned that helped me the most during thetumultuous teen years of my child. The first picture (below) is what I envisioned parenting my teenage children would be like: it would only get harder as they grew older, and I would eventually be drowned in overwhelming challenges.

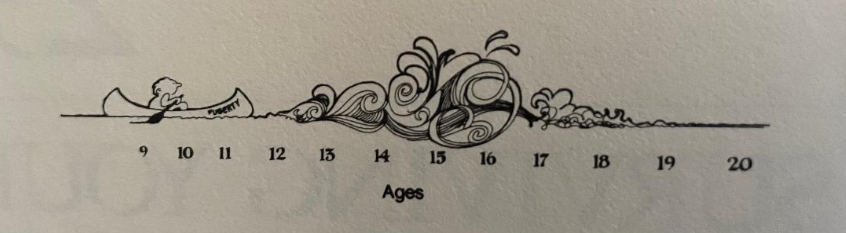

However, I learnt that what’s shown in the second picture (below) is how it’s more likely to be like, and what I actually experienced: their teenage years would be tough but the waves will eventually calm. My role as a parent is to just be there for them during this period, when they need me.

As I end this article, my mind goes back to the countless times I have failed in my parenting journey. But my kids have been forgiving as yours will be too.

Every day is a new opportunity to get things right and to be that great parent we wished we had. If you feel you need help and emotional support with your parenting journey, please do reach out to EMCC; our counsellors are here to help and support you.